Tilework, Tanneries, and Getting Lost in the Medina

From colorful riads to the maze-like medina, Fes felt like stepping back in time. Known as Morocco’s cultural and artisan capital, this city in the northeast has a deep sense of history that you feel the moment you step inside its walls. Over two days, I wandered narrow alleys, watched craftsmen at work, explored ancient gates and tiled courtyards, and visited one of the oldest tanneries in the world. Here’s how I spent two days in Fes exploring the medina, meeting artisans, and discovering Morocco’s cultural heart.

Planning a longer trip through Morocco? This post covers Days 2 and 3 of my journey. You can start with 15 Days in Morocco – Part 1: Cities, Mountains, and Medinas and continue on with Part 2: Sahara Nights, Coastal Towns, and Marrakech.

Fes, in Morocco’s northeast, has a deep sense of history you feel the moment you step into the medina. Known as the country’s cultural and artisan capital, it’s the kind of place that immediately feels different. The old medina, Fes el-Bali, is a UNESCO World Heritage site and one of the largest car-free urban areas in the world. The streets are narrow and winding, and it feels like they haven’t changed much in centuries.

In the medina, you’ll pass open workshops where metal is hammered by hand, narrow alleys lined with stalls, and people going about their daily routines. One turn might take you to a spice market, another to a quiet courtyard or a rooftop view. It’s easy to get lost, but that’s part of the experience. What stands out most is how much of the old craftwork—tile-making, leather tanning, weaving—is still happening right in front of you.

In the early evening, we arrived at Eden at Palais Amani, where we’d be spending the next two nights. The building retains elements dating from the 17th century, though it was partially rebuilt in the 1920s after major damage and then fully restored between 2006 and 2010. This was the first of several riads we’d stay in over the coming weeks. Like many traditional Moroccan riads, it centers around a courtyard garden, with rooms lining its perimeter over multiple stories—blending historic design with modern comfort.

Eden at Palais Amani, was gorgeous: colorful tilework, carved wood, and intricate details everywhere. On arrival, we were greeted by a hotel staff member wearing a fez and traditional dress, carrying a large silver tray with a silver teapot filled with Moroccan mint tea and a plate of traditional cookies—haribba and fakoua. The tea—sweet and poured from a height into small glasses—quickly became something we’d be offered everywhere we went.

My room (which I shared with a fellow traveler) was large and spacious—two double beds and a sitting area overlooked the courtyard. There was a side door out to a private patio and another set of double doors leading to a larger upper area. It was clear they put a lot of care into making everything feel special. In our room was a tray with a basket filled with fresh fruit.

Later that evening, we had dinner at Restaurant Palais la Medina, a beautifully restored riad that now houses both a hotel and a restaurant. The setting was just as stunning as where we were staying—more colorful tilework, carved plaster, and arched doorways. After dinner, we enjoyed Berber music and dancing, which felt like the perfect introduction to Fes.

Breakfast at the riad was what they called “Moroccan pancakes”—a mix of msemen and harcha, two types of griddled breads that show up all over Morocco. One was soft and flaky, the other more like cornbread, both perfect for dipping. Ours came with a simple lentil and tomato soup on the side, which was a hearty way to start the day.

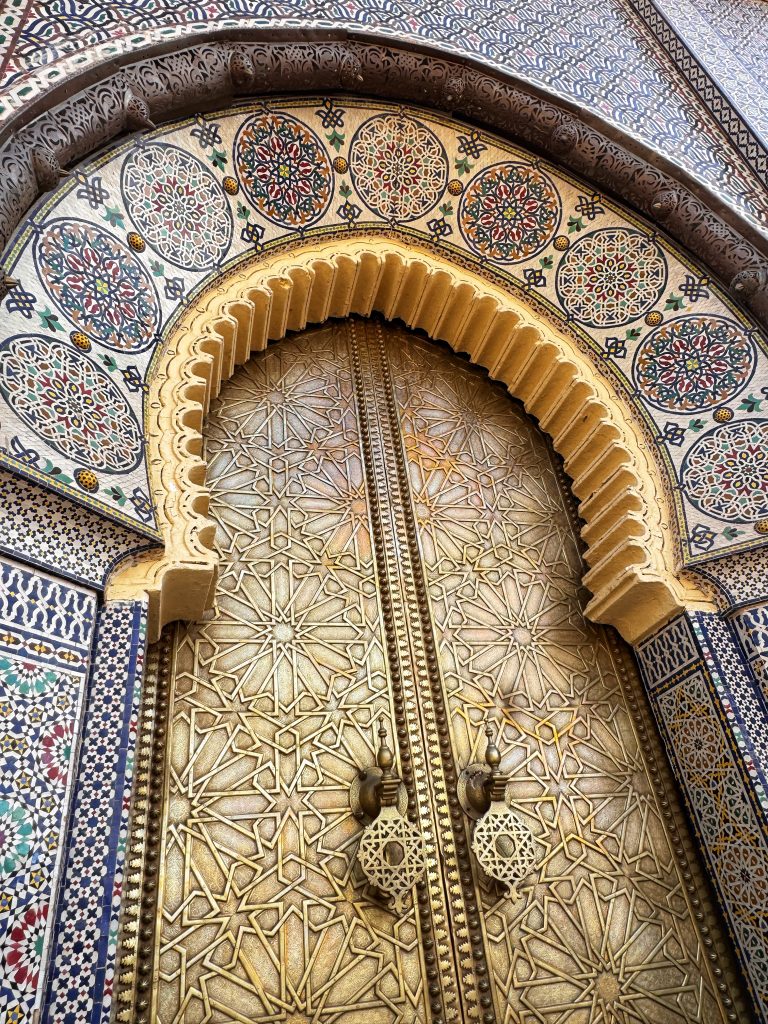

Then we boarded the van and headed outside the medina, starting at the Royal Palace in Fes el-Jdid. You can’t go inside, but just seeing the gates makes it worth stopping. These aren’t gates in the usual sense—they’re massive brass doors, known as some of the most famous in Morocco. There are seven in total, lined up side by side. The number seven carries symbolic meaning in Moroccan culture, tied to spirituality and protection.

Each door is huge and covered in intricate brass relief work. The patterns catch the light, and up close you can really see the depth and texture of the designs. What stood out most were the door knockers—heavy brass with delicate, star-shaped cutouts worked into them. They were beautiful, but they also felt like part of the larger design, blending in with the doors themselves.

Surrounding the doors, the walls are covered in colorful zellij tilework, bordered by carved plaster arches. It’s not just the doors that are impressive—it’s how everything frames them. The combination of geometric patterns, bright colors, and detailed carving is almost overwhelming, but in a way that makes you want to keep looking.

From there, we passed Bab Semmarine, one of the old city gates. t’s impressive—solid, symmetrical, and full of quiet authority. Gates like this are part of what defines Fes, marking transitions between neighborhoods while reminding you how long this city has stood. Bab Semmarine is also home to a handful of white storks (Ciconia ciconia), who’ve made their nests high on its towers like they own the place.

Before heading back inside the medina, we stopped at Poterie de Fès, just outside the old city walls. This is where traditional Moroccan ceramics and zellij tiles are still made by hand, using black clay that’s unique to the Fes region. We watched artisans shaping pottery at old-fashioned wheels, while others hand-painted tiles in classic Moroccan patterns. The signature tagine pots were everywhere, stacked in rows—used for the slow-cooked stews found all over the country.

But the workshop produced more than just tableware. There were mosaic fountains, tiled tabletops, fireplaces, and hearth surrounds, all decorated in the geometric patterns and deep colors that seem to show up everywhere in Morocco. What stood out most was how much of the work was still done entirely by hand, using the same methods they’ve used for generations.

Finally, we drove up to Borj Sud, a fortress overlooking the city. From up there, we had one of the best panoramic views of Fes. The entire medina stretched out below—tightly packed rooftops, narrow alleyways you could barely see between them. In the distance, on the opposite hill, were the Marinid Tombs.

It felt like Fes was spread out between those two high points—Borj Sud on one side, the Marinid Tombs on the other, both quietly watching over the city.

Then we headed into the medina. Even though it was a Friday—the weekly holy day in Islam, when many shops close—there were still plenty of stalls open and people out. We passed carts piled high with sticky, honey-soaked pastries and nut-filled sweets, all glistening under small lamps. Buckets of khlii (traditional preserved meat packed in fat) were stacked nearby, though I didn’t linger there.

Even with many of the market stalls shuttered, the medina felt alive. The smells shifted as we walked—spices, sugar, leather, and sometimes things less pleasant. It’s the kind of place where you can wander without much of a plan and still feel like you’re seeing something. Narrow lanes, old wooden doors, tiled walls, and unexpected courtyards tucked away behind them.

Eventually, we made our way to lunch at Darori Resto. From the outside, you’d never guess how beautiful it is inside: colorful tilework, carved wooden doors, and all those classic Moroccan architectural details. It felt more like being invited into someone’s home than a restaurant.

Our table was set with patterned blue plates and traditional cloth napkins embroidered with a Berber design. Lunch started with what’s pretty typical in Morocco—a spread of small salads. There were warm lentils in a spiced sauce, roasted beets, marinated olives, carrots with cumin, green beans tossed with onions, and chunks of seasoned pumpkin.

All of it came out at once, filling the table. I think that’s one of the things I love most about eating in Morocco: everything feels shared, like it’s meant for conversation.

After lunch, we visited the Zaouia of Moulay Idriss II, one of the most important religious sites in Fes. Non-Muslims aren’t allowed inside, but even standing at the entrance, it was impossible not to be impressed. The architecture was incredible—walls completely covered in intricate zellij tilework, arches edged in delicate carved plaster, and dark wooden doors with patterns so detailed you could stand there for ages just trying to take them in.

Through the open doorway, we could see the main courtyard: a marble floor, a small central fountain, and more tilework covering every surface. The ceilings were just as detailed, with carved wood and geometric patterns extending above the arches. It was almost overwhelming—so much detail in every direction that it was hard to know where to look.

From there, we headed to the Chouara Leather Tannery. As we got closer, the smell became impossible to ignore—strong and sour. A narrow river, the Oued Bou Khrareb, runs right past the tannery and honestly didn’t help. It’s been used for centuries to carry runoff from the medina, so with that and the leather processing, the whole area just reeked. We passed cars and carts with animal hides draped over them, drying in the sun like it was no big deal.

Inside the tannery, we were handed sprigs of mint to hold under our noses—which helped… kind of—and then led to the viewing area, where you got a full look at all the vats below. I’d seen photos before, but seeing them in person was something else.

From where I stood, I could see the whole layout. There were more than a hundred stone vats—some filled with a chalky white liquid used to clean and soften the hides, others holding bright dyes: reds, yellows, browns, blues.

Chouara is actually one of three traditional tanneries still operating in the Fes medina—but it’s by far the biggest and the one most people come to see. It’s also the oldest, with records going back over a thousand years. And honestly, the process hasn’t changed much. The hides are soaked to remove hair, cleaned, dyed, dried, and finished with oils. It takes weeks.

They showed us different types of hides—cow, sheep, goat, and camel—and let us feel the difference. The softer ones, like sheep and goat, are used for jackets and handbags. Cow and camel are tougher, so they’re used for shoes, belts, and bigger pieces. Some of the leather is still tanned using natural, plant-based methods, alongside the more traditional ones.

After watching for a while, we were taken down into the tannery’s shop. Leather in every color imaginable—coats, bags, wallets, shoes, ottomans—was stacked and hanging everywhere. And if they don’t have what you want, they’ll custom-make it. You pick the leather and the color, they take your measurements, and ship it to you when it’s ready.

By the time we left, I felt like I’d seen both sides of the place—the raw, physical work happening in the vats, and the polished, finished products just a floor below.

From there, we stopped at a few scarf shops in the medina. Those of us who hadn’t brought scarves with us wanted to buy one—apparently, we’d need them for our upcoming camel ride in the desert, where scarves are worn to protect against the sun and sand. There were rows of scarves to choose from, in every color and pattern imaginable.

Some were lightweight cotton, others were silk blends, and the quality ranged from simple, practical scarves to ones that felt more decorative.

Trying to choose just one felt impossible—there were scarves in every color and pattern imaginable. Eventually, indecision won, and I left with a light green one with colorful tassels (which I still have, because of course I do).

Still full from lunch, I decided to skip dinner and have a hammam instead (yes, I know—I’m getting hooked. Let’s call it research).

I left the hammam feeling clean, calm, and a little dazed—in the best way. It was the perfect ending to a day that gave me so much to take in.

Next stop: the cedar forest and a night in Ifrane, also known as “Little Switzerland.

Hi, I’m JoAnne—writer, wanderer, and lover of places that surprise me. I’ve traveled to 60+ countries (and counting), usually with a camera in one hand and a notebook in the other. I’m drawn to mosaics, markets, and mountains, and I write to remember what moved me. When I’m not traveling, I’m working on my blog Travels Afoot, trying new creative projects, or planning my next adventure.