There was always something about Morocco that drew me in. The colorful tiles, patterned doorways, carved arches—it all looked so visually striking. But it wasn’t just the design. I was curious about the mix of cultures: Spanish, Islamic, Berber, and French influences, layered together but still distinct. I pictured that mix shaping everything—not just the buildings, but the food, the music, and daily life itself.

Of course, actually being there felt different. Which makes sense. You can look at photos, but it’s definitely not the same as standing in the middle of it—hearing the call to prayer, smelling spices in the market, tasting the food, seeing the colors right in front of you. All your senses are involved. Nothing felt flat or abstract—it was all full and present.

Morocco also reminded me a little of Tunisia—the warmth of the people, the architecture, and the way life spills into the streets felt familiar. But Morocco felt bigger. Not just in size, but in how much the landscapes changed as we traveled. In Tunisia, things felt more consistent: desert towns and Mediterranean coast. Morocco kept shifting—mountains, desert, valleys, coastal towns, and cities that each felt different from the last.

I actually arrived a few days early, flying into Casablanca and then heading to Chefchaouen—the famous blue city—for two days. You can read more about that part of my trip [here]. After that, I returned to Casablanca to meet up with the group and start the 15-day journey from the city to the desert and out to the coast.

I traveled as part of a small group with AdventureWomen—twelve women from across the U.S.—led by our local guide Sara, whose humor and personal stories added depth to every stop along the way.

Somewhere between the mountains and the desert, I also became mildly obsessed with dates and olives. Another woman and I made a habit of finishing off every olive bowl that showed up at meals. No one else seemed to mind—more for us.

This post is the overview of that journey—a look at where I went, what I saw, and why Morocco stayed with me long after the trip ended.

The group trip officially started in Casablanca, where most of us were meeting for the first time. We spent the night there at Idou Anfa Hotel, but Casablanca itself wasn’t really the focus—it was more of a starting point before we moved on. Still, we did visit one of the city’s most famous landmarks: the Hassan II Mosque. It sits right on the edge of the Atlantic and is massive.

The tallest minaret in the world rises above it, and parts of the floor are glass, so worshippers kneel directly over the sea. Inside, every detail—from the carved ceilings to the intricate tilework—felt both grand and delicate at the same time.

Later that day, I crossed something off my personal list: my first hammam experience. I’d been curious for a while (and honestly, a little unsure what to expect), but it turned out to be one of those travel moments I’m glad I said yes to. (You can read more about that experience [here].)

Knowing I had a long drive ahead the next morning, I opted for a quiet evening. I went up to the Uptown Lounge at Idou Anfa Hotel, one of the upper-floor restaurants with sweeping views of Casablanca. I had a drink and some hummus—part of a little mezze spread—and just took it all in. It was kind of perfect.

From Casablanca, we made our way inland, stopping in Meknes, one of Morocco’s imperial cities. Our visit was short, but it gave us a good taste of the city’s history and craftsmanship. We started by visting the Mausoleum of Moulay Ismail. Moulay Ismail was the sultan who helped make Meknes a capital in the 17th century, and the mausoleum built in his honor is beautiful.

We wandered through tiled courtyards, past marble fountains and ornate brass chandeliers, and admired the carved stucco and colorful mosaics that covered nearly every surface. Non-Muslims can’t enter the actual tomb room, but much of the site is open to visitors.

We stopped at Bab Mansour, Meknes’ most famous gate. It’s huge—decorated with colorful zellige tile, carved plaster, and marble columns—and once marked the entrance to the imperial city. Like many Moroccan landmarks, it’s both imposing and intricate at the same time.

From Meknes, we continued to Volubilis, where the ruins of a once-thriving Roman city sprawl across rolling hills. It felt surreal to be walking among ancient columns, crumbling stone arches, and floor mosaics that have survived for centuries. Some of the mosaics were surprisingly intact—still showing detailed patterns and scenes from Roman mythology.

Later that morning, we visited a small women’s embroidery cooperative, where Amazigh (Berber) women stitched geometric designs onto dark fabrics—each pattern precise and symbolic. Not far from there, we watched a metal engraver carefully etch floral designs into a brass plate using nothing more than small hand tools. The work was incredibly detailed.

By midday, we were welcomed into the home of a local family for lunch. We started, as is traditional, with sweet mint tea. Then came a Berber omelet—eggs, tomatoes, and cheese cooked together in a tagine pot. Simple, filling, and honestly one of my favorite meals of the trip.

In the early evening, we arrived at Eden at Palais Amani, where we’d be spending the next two nights. This was the first of what would be several riads we’d stay in over the next few weeks. Like many traditional Moroccan riads, it was built around a central courtyard, with several stories of rooms opening onto the inner space.

Eden at Palais Amani was gorgeous: colorful tilework, carved wood, and intricate details everywhere. On arrival, we were welcomed with Moroccan mint tea and a plate of traditional cookies. The tea—sweet and poured from a height into small glasses—became something we’d be offered everywhere we went. You may know from some of my other posts that I’m more of a coffee drinker, but I have to admit, I was really starting to love the mint tea—such a beautiful tradition, and everyone who served it seemed to make it feel special.

Later that evening, we had dinner at Restaurant Palais la Medina, a beautifully restored riad that now houses both a hotel and a restaurant. The setting was just as stunning as where we were staying—more colorful tilework, carved plaster, and arched doorways. After dinner, we enjoyed Berber music and dancing, which felt like the perfect introduction to Fes.

The real experience of Fes, though, started the next morning. (More on that soon.)

Our full day in Fes (sometimes spelled Fez) started with a guided walk through the medina—a maze of narrow streets, hidden courtyards, and bustling souks.

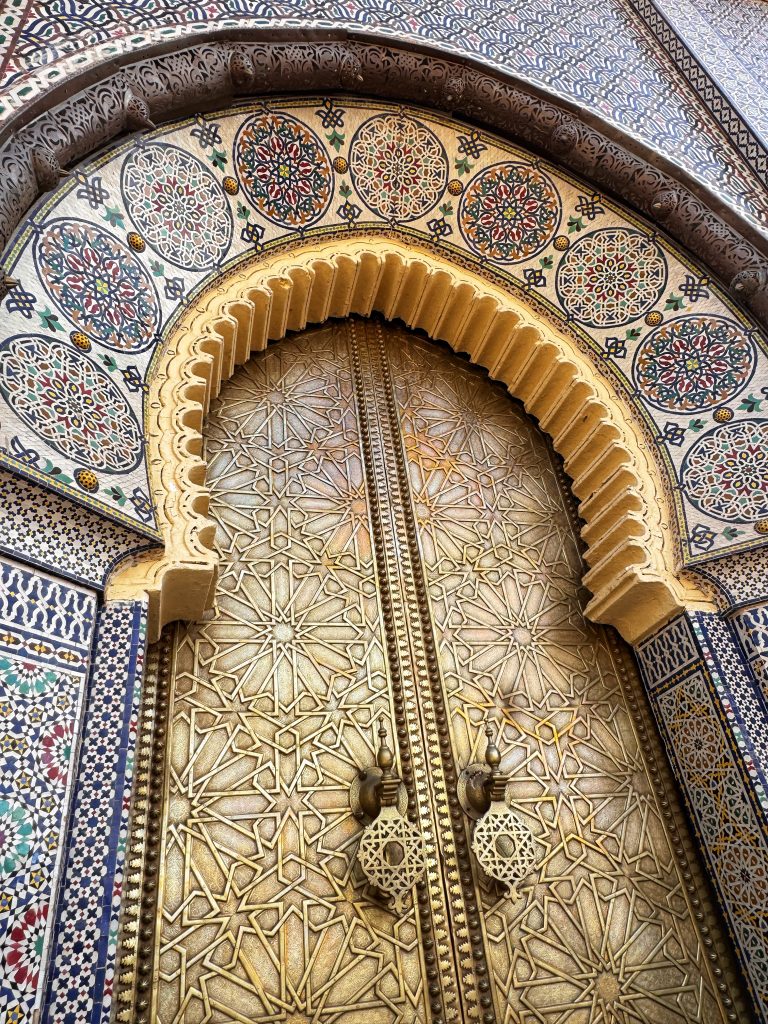

Then we loaded into the van and headed to the Royal Palace of Fes—or at least the outer walls of it. The palace isn’t open to visitors, but we stopped to see the massive golden doors, set into walls decorated with colorful zellige tiles and carved plasterwork. The doors were huge—ornate but solid, like they hadn’t been opened in years.

From there, we walked past Bab Semmarine, one of the main gates into the medina—and a favorite nesting spot for storks, their twiggy homes tucked along the upper edges—before continuing deeper into the maze that is Fes el-Bali.

Later, we visited Poterie De Fes, a ceramic workshop where artisans were hand-painting tiles and shaping pottery on old-fashioned wheels. One of their most popular items was the classic Moroccan tagine dish, used for the slow-cooked stews found all over the country.

But they made much more than just tableware—the workshop also produced tiled hearths, mosaic-topped tables, and decorative pieces, all painted with the bold geometric patterns typical of Moroccan design. It was fascinating to watch the work being done by hand, knowing how much of Morocco’s architecture and décor still relies on these traditional skills.

We stopped for a traditional Moroccan lunch, Darori Resto, before visiting the Chouara Tannery—one of Fes’s famous leather workshops, where hides are still dyed using centuries-old methods. And yes, they handed us sprigs of mint to help with the smell. And yes—I really did need it.

You can read a more detailed blog about my time in Fes [here].

Before leaving Fes that morning, we stopped at a local market to pick up supplies for the picnic we’d have later in the day—fresh bread, tomatoes, cheese, olives, and fruit.

Leaving Fes behind, we drove toward the Middle Atlas Mountains. Our destination: Ifrane, sometimes called “Little Switzerland” for its alpine-style houses and tidy street.

We stopped for a simple picnic lunch in the cedar forest within Ifrane National Park: the bread, cheese, and olives we’d picked up that morning. This area is home to one of the largest cedar forests in North Africa—and to a large population of Barbary macaques.

We’d seen them everywhere on the way in. It was hard to find a spot where they weren’t already lurking nearby. Eventually, we found a relatively quiet patch and rented a big rug to spread out on the forest floor, thinking it would be a peaceful place to take a break.

The cedars themselves were tall and impressive, but the forest wasn’t quite what I expected. I’d pictured something dense and green, like a pine forest, but this felt more open and dry, with scattered trees and dusty ground between them.

As we set out our picnic, we had to form a tight circle around the food. The monkeys were already watching us. Within minutes, they began to close in. They weren’t shy. One reached right through a gap in our circle and grabbed a whole tomato. He sat just off the edge of our rug, tomato in hand, calmly eating it like he’d earned it.

It did not make for a relaxing picnic. I kept glancing over my shoulder, half-expecting one to jump out of a tree behind me and on to my back. It wasn’t my idea of an enjoyable picnic—but it was definitely a memorable one.

We also took a short hike through the forest with a naturalist, who shared a bit about the cedar trees and local wildlife along the way. Then we continued on to Azrou, where we stayed overnight.

The next morning, we set out for the Ziz Valley. The drive itself was part of the experience, with changing landscapes that kept pulling me to the window: mountains giving way to valleys, then stretches of arid, rocky terrain.

We made a stop in Midelt, a small town surrounded by apple orchards and mining areas. It felt like one of those in-between places—a quiet break in the drive. We had lunch at a local home, sitting outside in the orchard at a low table. Two women cooked couscous and tagine—vegetable for me, meat for the others—while we ate under the trees on plastic stools. Simple food, but good. And of course, tea followed the meal—because when you’re in Morocco, there’s always tea.

As we drove on, the scenery shifted again as we reached Errachidia, known for its vast palm groves and date production. The air felt warmer, the colors dustier. We checked into Maison Vallée du Ziz, a relaxed guesthouse overlooking the valley, where we stayed for two nights.

Breakfast and dinner were served here—always simple, traditional Moroccan meals. And being surrounded by a palmeraie, it wasn’t surprising that every meal ended with a plate of fresh dates.

The staff at the guesthouse were friendly and attentive, and the whole place had an easy, welcoming feel.

Behind the guesthouse, a path led down through the palm groves (palmeraie), following the edge of the valley. It was the kind of place where you could take a quiet walk before dinner, surrounded by palm trees and the sound of birds.

In the morning, we met a local guide and explored the palmeraie—walking narrow dirt paths between date palms, olive trees, and small fields where families grow what they need—and learning about the valley’s irrigation systems, which made the whole landscape possible. The irrigation channels—some of them centuries old—still supply water to each small plot.

At one point, we came across a couple standing at the base of some date palms while a man was high above them, perched in the branches, harvesting dates. He wasn’t tossing them down—instead, he sent them down in a woven basket lowered from the tree. The woman handed us some of the fresh dates to try, straight from the tree. They were so good—soft, sweet, and completely different from the dried ones I was used to.

As lunchtime neared, we headed to a women’s cooperative in the village of Foukania, where couscous is still made entirely by hand (I wasn’t able to find its formal name). Inside a simple room lined with rugs, we watched the women roll and sift semolina in large shallow bowls, their movements rhythmic and unhurried. Occasionally they sang as they worked. There was something communal and timeless about it—the kind of skill passed down through generations, now preserved not just as tradition, but as a livelihood for the women of Foukania.

Afterward, we sat down to eat: couscous served two ways—vegetable for me, and meat for the others—along with fresh bread, mint tea, and dates from the valley. We ate outside at long tables. It was simple food, but easily one of the more memorable meals of the trip.

You can read more about that visit—and life in the Ziz Valley—in my separate blog post [coming soon].

Leaving the Ziz Valley behind, we headed toward Merzouga and the Erg Chebbi dunes—the gateway to the Sahara. The landscape shifted again as the golden sand came into view, stretching as far as the horizon.

In the afternoon, we stopped in Et-Taous for a leisurely lunch, where we enjoyed traditional Medfouna also know as Berber pizza while listening to live Gnawa music. The musicians played the guembri, a three-stringed bass lute, alongside krakebs, large metal castanets that added a rhythmic clanking to the atmosphere. The music, with its deep, resonating tones and rhythmic beat, created a perfect backdrop for the experience. The pizza—made with flatbread and topped with a savory mix of vegetables and spices—was simple but absolutely delicious. The music added an extra layer of authenticity to the experience, setting the tone for the adventure ahead.

In the early evening, we were driven to Rissani, where we met our camels and the cameleers who’d be leading us into the desert. The camels were already kneeling in the sand when we arrived—calm, silent and saddled. Mounting up was more awkward than graceful. You swing a leg over while the camel’s kneeling, then grab tight to the front of the saddle—because you’ll need it.

When the camel stands, it’s not a gentle rise. Its back legs straighten first, tipping you sharply forward, hard enough that you feel like you might pitch straight off. You have to really hold yourself in place. Then, just as suddenly, the front legs rise, rocking you backward in one jarring motion. It’s not slow, and it’s not smooth.

By the time the camel is fully upright, you’re gripping the saddle, maybe holding your breath, and only then realizing how high up you actually are—swaying with every step as it starts to move.

The ride itself was calmer than I thought it would be. It felt more like being carried than riding, like moving slowly across waves of sand. The light kept changing as we rode—late afternoon fading into evening, long shadows stretching across the dunes.

Eventually, we reached Sahara Sky Luxury Camp—a group of tents that looked traditional from the outside but felt surprisingly solid and homey inside. Mine had wood-style floors, a real bed with blankets, and even a private bathroom with a hot shower. It didn’t feel like camping. If anything, it felt like someone had picked up a hotel room and dropped it in the middle of the desert.

Later that evening after dinner, we sat around a small fire and listened to traditional Berber music and drumming, with a little dancing. Sitting out there under the stars, surrounded by dunes, was beautiful—even if the whole experience felt a bit polished and touristy compared to my simpler, more authentic desert stay in Tunisia.

Still, something about that night stuck with me—the way the firelight lit up the tents, the steady beat of the drums, the quiet of the sand all around us. From the camel ride into the Sahara to sleeping under the stars, this was the end of Part One—halfway through Morocco, and only just getting started.

Continue reading Part Two – From the Sahara to the Coast [here].

Hi, I’m JoAnne—writer, wanderer, and lover of places that surprise me. I’ve traveled to 60+ countries (and counting), usually with a camera in one hand and a notebook in the other. I’m drawn to mosaics, markets, and mountains, and I write to remember what moved me. When I’m not traveling, I’m working on my blog Travels Afoot, trying new creative projects, or planning my next adventure.